George Daniels Anniversary Watch; the Master's Final Masterpiece

In his book All in Good Time, the watchmaker George Daniels writes that ‘It was one of these watches that Sam Clutton carried with him during his journey to Japan. After a month, it was under one second slow.’

He was referring to a pocket watch with his Double-Impulse Chronometer escapement. Clutton was his mentor, fellow watch expert and the owner of the very first watch Daniels ever made.

Quite the odyssey, 30 days to Japan and back in the early 1970s, wearing a unique hand-made English watch.

Since then, much has been written about Daniels watches, especially by those appreciating them at the rare times they appear in auction. But what is a Daniels really like day-to-day? If Clutton were our contemporary, what Daniels might he take on a long global journey?

The final watch George created was the Daniels Anniversary. This is a series of 35 numbered pieces in yellow gold. There is an option to produce a further four each in platinum and white gold, although only a couple of those have actually been made.

The series was created to celebrate 35 years since Daniels invented the co-axial escapement. Planning began in 2008, with the first metal being cut in 2010. George’s erstwhile pupil and eventual successor, Roger Smith, was commissioned to ensure that the watches were completed and delivered to their select owners, in accordance with George’s wishes.

The Daniels Anniversary was made entirely by hand in the Isle of Man studios of Roger Smith. When Roger exhibited the first example at Salon QP in London in 2012, the watch caused an absolute sensation. Collectors had long dreamed of this one last chance to obtain a new Daniels masterpiece.

___________________________________

The Daniels Anniversary has a stylistic predecessor: the four-minute tourbillon chronograph that he made in 1991. The first photo below, kindly supplied by SJX Watches, is the 1991 Tourbillon. The second photo (click or <<< swipe across to see the two images) is the Daniels Anniversary.

See the strong resemblance; the main dial is pitched slightly above the horizontal centreline. Near the top of each is the state-of-wind indicator, with overlapping subsidiary dials at lower left and right. In the tourbillon these are the chronograph indicators and seconds respectively, and date and seconds in the Daniels Anniversary. At 6 sits the all-important Daniels signature, in an applied escutcheon.

The Anniversary watch is 40mm diameter and 12mm thick. The case is simple and clean, allowing attention to be drawn to what Daniels always considered the most important thing: the time.

___________________________________

Another comparison between the first-ever Daniels wristwatch from 1991, with the present Daniels Anniversary (swipe across or click). Both dials are a masterclass in perfect engine-turning. The 1991 watch has solid silver chapter rings, and the Anniversary has them in solid gold. The black-polished seconds counterpoise is another distinctive Daniels feature, as is the unambiguous hour hand. First image courtesy of SJX Watches.

___________________________________

Roger Smith and his team still build watches one at a time by hand according to what's now come to be known as ‘The Daniels Method.

Within this simple phrase is woven a staggering degree of skill and an obsessive amount of work. It describes the process where one man masters all the dozens of individual specialist avenues of the craft traditionally necessary to produce a watch. Before horological industrialisation, watchmaking demanded hand-skills by experts who took 8–10 years to become proficient at their narrow branch of craft. Those experts would spend a lifetime plying only that single discipline. Daniels mastered all of these, perhaps the first person in history to do so.

It's easy to underestimate the value of being the first. These days just about every young horologist is an aspirational hand-maker of watches. Swiss brands now come up with an endless stream of interesting escapements, materials and other watch technology. Within seconds we can summon high-resolution photos of hundreds of high-craft watch movements from anywhere in the world.

But Daniels did what he did all on his own, without any terms of reference to contemporary peers. If he wanted to consult a book on how to make something, he'd have to first write it. When he wanted to study macro photos of antique watches, he'd have to shoot them himself.

Not only are his watches pinnacles of craft, but his knowledge of the theory of horology was also unsurpassed. The practical instruction he gives in the book Watchmaking is underpinned by a cornucopia of formulae describing gear teeth, springs, and astronomical wheel trains. Few people cross that craft-theory boundary.

Neither was Daniels a dusty 'man-in-a-shed' misanthropic nerd. He rebuilt and raced vintage cars, discoursed into the early hours at his London club, and socialised with the world's greatest collectors from Buckingham Palace to Geneva.

Daniels was very careful with his choice of client. Of all his watches, he only ever made one to commission. He pre-selected who would receive a Daniels watch, and like Clutton, they were all people who'd wear and enjoy his masterpieces, not lock them away in a cold vault!

“It's not much good making watches for people who just put them in bank vaults!” – George Daniels

Ease of reading the time comes from the refined design of the gold hands and solid silver engine-turned dial. The engine-turning was done on the original Daniels rose- and straight-line engines.

Daniels points out the reason for the engine-turning: to create variations of surface. Rather than being decorative, the engine-turning patterns recede from the eye in use, instead manifesting themselves as subtle differences in contrast as light reflects off the dial’s different zones. This makes it makes the dial more legible by increasing contrast against the hands, which stand out clearly at a glance.

The effect only works because of the guilloche's absolute perfection of execution. The widths, depths, and crest-matching of every incision meet in flawless exactitude; any variation would break the evenness and therefore draw the eye. The engine-turned dials made by Roger’s studio are as good as any I have seen, with the dial of his GREAT Britain watch still being one of the pinnacles of that craft.

<<< Swipe or click

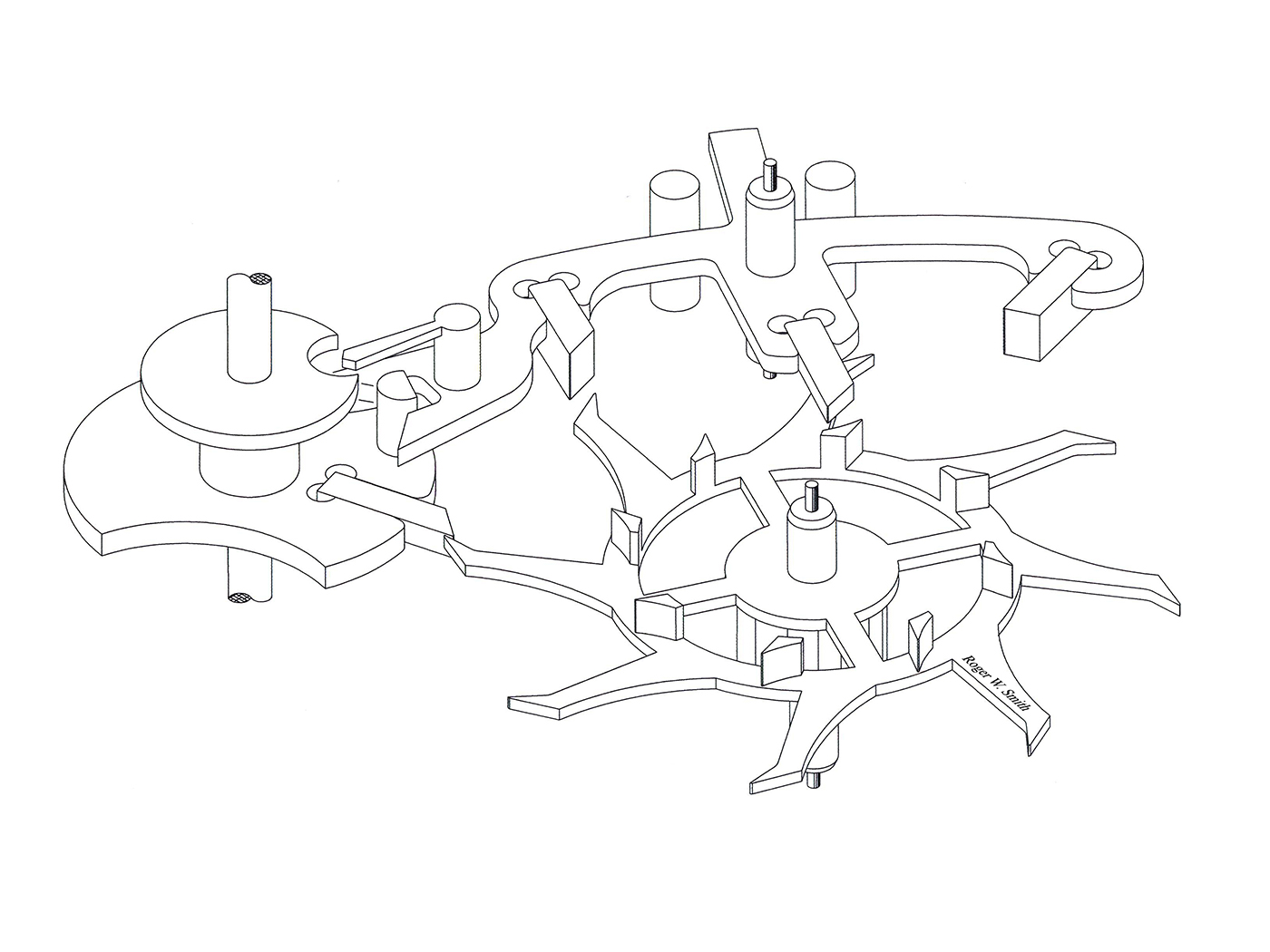

Of course the watch has a co-axial escapement. Devised by George Daniels as a way to increase service intervals and reliability due to it not relying on regular fresh oil, the escapement has enjoyed a number of improvements under Roger Smith's direction. Its two sets of teeth are now carved into a single blued-steel wheel. This patented revision is lighter and more concentric than earlier two-piece types, difficulties that even Swiss escapement makers Nivarox-FAR struggled to eliminate. Swipe between Roger Smith's drawing here and a photo of the escapement in the Daniels Anniversary.

The balance is made of beryllium copper, a hard alloy that's resistant to deformation and is a good match with temperature-compensating balance springs.

Click or swipe the image.

The state-of-wind ("power reserve") indicator is driven by a differential screw mechanism, something that Daniels loved to use in his watches, and which he illustrated in Watchmaking.

This device is elegant and simple. A steel gear wheel twists a threaded arbor when the watch is wound (a). This raises a disc-like steel "nut" (b). As this rises, it pushes aside an arm that has a sloped nose (inset). This is linked to the state-of-wind hand on the front of the watch, swinging it to the left when the watch is wound, and back to the right as it runs down.

A similar pair of slope-nosed arms connected in a steel "Y" arm (c) also run along the "nut". This clicks right and left as the watch is wound and unwound. This locks and unlocks the balance stop device. The whole arrangement is compact and reliable and reflects the purposeful directness of its designer.

This system represents another feature of the work of Daniels and other respected pioneers: consistency and continuity of execution. Daniels used a screw differential all the way back in 1973 on the watch he made for Professor Thomas Engel. The following year he used it again in the Elsom II. Once he’d adopted something, he stuck with it, refining it, but keeping true to his fundamental interpretation.

As much as this applies to the technical details of Daniels watches, it applies equally to their appearance. His first watch had a pivoted detent escapement. Ten years and sixteen watches later, he had developed the co-axial escapement, but just try to tell them apart at a glance. His watches have a visual continuity that weaves them into a unified body of work. Without resorting to attention-seeking fancy decoration, each watch is instantly and profoundly recognisable as a Daniels.

On the wrist, a Daniels is enigmatic. It has irresistible presence, obviously an important watch, but clearly not one of the mainstream. It is reassuringly heavy, for all its grace and lightness of style. It is high precision, more accurate than Sam Clutton's pocket watch.

Clutton will doubtless have felt moved when contemplating hand-crafted watches. Knowing how long somebody spent devoted to the object's construction, the countless re-starts. It is humbling to consider the maker's tireless iterative improvements aimed at presenting to his patron an object as perfect as conceivable. What a great time to be a collector when outcomes like this are possible. This is the real journey, more exciting and difficult to reach than even Japan.